Children’s Voices for Change

This report presents the findings of the ‘Children’s Voices for Change’ project.

A rights-based approach to understanding and implementing effective supports for children and pre-adolescents as victim-survivors of family violence.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement of Country

We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first peoples and Traditional Owners and custodians of the lands on which we live, work and undertake our research. We pay our respects all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, past, present and emerging. We also acknowledge the ongoing strength and resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the vital role of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people as leaders in their communities and across Victoria in addressing domestic, family and sexual violence.

Funding acknowledgment

Southern Cross University acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government. This research has been funded by the Victorian Government’s Family Violence Research Program – Phase 1 Grants Round, led by Family Safety Victoria (FSV).

Children and young people who generously shared their time, expertise, insights and experiences have made this research possible. We thank the 23 children and young people who participated in the Children’s Activity; Lachlan, Geordie and Xaydd who took part in the collaborative workshops to develop the Children’s Feedback Tool; and the Youth Advisory Group – Kirra, Tash, Liam and Millie – who continuously shared their wisdom and guidance throughout the project. We also thank the 320 practitioners who responded to the survey to share their perspectives and experiences working with children and young people; members of the Project Advisory Group – Aileen Ashford, Rachel Carson, James McDougall and Meena Singh – for their valuable practice insights and expertise that guided the design, delivery and outputs of this research

The Project

This report presents the findings of the ‘Children’s Voices for Change’ project, which applied a children's rights-based approach to understand what constitutes effective supports for children and pre-adolescents aged up to 13 years (referred to in this report as ‘children’) as victim-survivors of family violence in their own right.

This research project has engaged with children and young people as family violence experts by experience – as research participants, co-researchers and Youth Advisory Group members – to build a knowledge and evidence base that strengthens understandings of the diversity and distinctiveness of children’s experiences of family violence, and the effectiveness of services in meeting their needs.

The project reviewed existing research and analysed client data from The Orange Door, to understand children’s system pathways; surveyed practitioners who provide support services to children who have experienced family violence; conducted participatory research with children and young people who have accessed family violence support services in Victoria; and co-created a Children’s Feedback Tool through collaborative workshops with children and young people and practitioners.

Key Findings

Start listening. Don’t think you know. You can’t see us as victims in our own right unless you actually listen.

Molly, 11

5. Various systemic barriers to supporting children as victim-survivors in their own right effectively persist:

- The specialist family violence service system is insufficiently resourced: practitioners and children alike highlighted concerns about long wait times to access services, staff shortages and high staff turnover, a lack of specialised programs and therapeutic interventions, insufficient case management periods, and a lack of practitioner expertise and confidence.

- Family law parenting orders hamper the effectiveness of family violence service responses and/or place children at risk of harm.

- Police responses to family violence incidents are experienced by children negatively, including due to police seemingly ‘siding’ with the person using violence, or failing to believe children or to respond adequately to their situation.

- The requirement for parental consent to engage with services can be used by the person using violence to prevent children’s access to support, as a form of control and ongoing abuse.

- Challenges persist for collecting data and evidence to understand children’s distinct, unique needs: The Orange Door data collection practices often attach a child’s case to that of an adult. There are no data available on the timeliness and effectiveness of The Orange Door sites’ engagement with children. ‘Unknown’ case numbers for children with disability and children who are culturally and linguistically diverse remain high.

- Financial support and housing stability are key unmet needs for children who have experienced family violence.

- Services do not always collaborate and communicate effectively to ensure that important risk information about children is appropriately shared and acted upon.

6. Services and systems must listen to, hear and understand children.

Children must be respected as capable of identifying and articulating their distinct family violence response and recovery needs, consistently with their evolving capacities and with appropriate direction and guidance.

Recommendations

There are 11 recommendations for consideration, to support the translation of the research findings into law, policy and practice. Click on the ▶︎ to explore each recommendation.

1. Youth Advisory Group

2. Specialised and targeted programs

3. Length of support periods

4. Capability-building for professionals

5. The Orange Door data collection

6. Cultural safety

7. Community awareness of family violence

8. Financial support and brokerage

9. Housing stability and crisis accommodation

10. Victoria Police practice resources

11. Children’s meaningful participation in family law decision-making

Study Design and Methods

This project was led by researchers from Southern Cross University (SCU), in collaboration with researchers from Swinburne University of Technology, and in partnership with Safe and Equal, and the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare.

The research was supported by a Project Advisory Group, comprising experts from across family violence and children’s rights policy, practice, research and advocacy; as well as a Youth Advisory Group, comprising four children and young people, aged 11 to 25, with lived experience of family violence, who were recruited through Berry Street’s Y-Change Lived Experience Program and Safe and Equal’s lived experience team.

Aims

1. To understand how children conceive their family violence response and recovery needs;

2. To identify supportive factors that facilitate meaningful engagement with children in a way that meets their needs and respects their evolving capacities;

3. To identify barriers to the development and operation of effective family violence support services for children as victim-survivors in their own right; and

4. To develop clear, practical capability-building resources to enable children’s meaningful, safe participation in family violence program design and service delivery, including measuring and monitoring the effectiveness of outcomes.

Research Questions

1. How do child victim-survivors of family violence currently engage with Victoria’s family violence service system? What are their pathways into and through the system?

2. Are there examples, across sectors and jurisdictions, of system responses that centre children in service design and delivery, that can inform the Victorian approach?

3. What do children identify as important in their family violence response and recovery needs?

4. What are supportive factors shaping, and barriers impeding, Victorian family violence service system responses to children as victim-survivors in their own right?

5. What ‘gaps’ exist between practice and what child victim-survivors identify as important and effective in meeting their needs?

6. How can a rights-based approach be used to inform the development and implementation of effective supports for children as victim-survivors, including needs assessment, service response and evaluation of outcomes?

A Children’s Rights-Based Approach

This research was informed by a children’s rights-based approach and children’s rights under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)

A children’s rights-based approach empowers and equips children to participate in decision-making processes about their family violence recovery and support needs, consistent with their evolving capacities and with appropriate direction and guidance.

It emphasises the strengths of each child, as well as the need for support services and systems to develop the capacity to meet their obligations to respect, protect and uphold children’s rights under the UNCRC (Article 4), particularly its four pillars:

- the right to non-discrimination (Article 2);

- the best interests of the child (Article 3(1));

- the right to life, survival and development (Article 6); and

- the right to participation (Article 12).

The children’s rights-based approach informing this project is underpinned by four fundamental principles (Dimopoulos, 2022; Stalford, Hollingsworth & Gilmore, 2017; Tobin, 2009; Freeman, 2010):

1. Children are active subjects with distinct rights and interests.

2. Children people have evolving capacities for decision-making.

3. Children and young people need appropriate direction and guidance to exercise their rights.

4. Children and young people must participate meaningfully in decision-making about their family violence response and recovery needs.

Article 19 of the UNCRC provides for children’s right to be protected from family violence and to receive effective supports as victim-survivors.

Project Phases

Phase 1

Desktop and literature review and The Orange Door data analysis

Phase 2

Survey of practitioners

Phase 3

Children’s Activity

Phase 4

Children’s Feedback Tool

co-creation

Phase 1

Desktop and literature review and The Orange Door data analysis

A desktop and literature review of the evidence base in Victoria and other jurisdictions for meeting the needs of children as victim-survivors of family violence in their own right.

An analysis of client data from The Orange Door to understand children’s system engagement pathways. Aggregated referral and case data from The Orange Door were provided by FSV for children aged 0 to 13 years for each financial year from 2017-18 to 2021-22. The data included case numbers for children across all The Orange Door sites; case numbers by demographic factors; referral sources; and case closure reasons.

Phase 2

Survey of practitioners

An anonymous, online survey of practitioners working in a range of service settings in Victoria, to identify factors influencing the effectiveness of family violence support services for children. A total of 320 practitioner responses were received and analysed quantitatively and qualitatively.

Phase 3

Children’s Activity

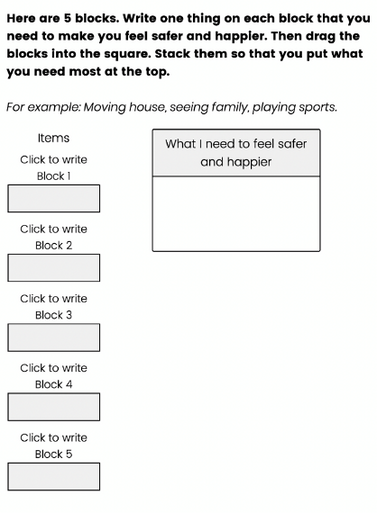

Participatory research with children and young people who are victim-survivors of family violence, through an anonymous, online engagement activity developed together with the Youth Advisory Group. The Children’s Activity included multiple choice, open-text and interactive questions, such as ‘dragging and sorting’ boxes to rank items and selecting an ‘emoji’ face to represent feelings.

- Recruitment: Children and young people aged 10 to 25 years, who have experience accessing family violence support services in Victoria when they were aged up to 13 years, and have an established relationship with a service provider or victim-survivor advocate network, were invited to participate.

- Consent: Participants aged 16 to 25 years could provide their own consent. Participants 15 years and under required the co-consent of a ‘trusted adult’ over 18 years of their choosing (such as a parent, guardian, family member, sibling, teacher, close friend or caseworker).

Phase 4

Children’s Feedback Tool co-creation

The research team hosted four online collaborative workshops with seven children and young people, to:

- Co-analyse the Children’s Activity responses from Phase 3; and

- To co-create and test a Children’s Feedback Tool.

The CHANGE Children’s Feedback Tool is intended for use by services who work with children and young people who have experienced family violence, to facilitate their meaningful and safe feedback and to inform practice development and ongoing workforce capability-building priorities. The Tool brought together findings from all phases of the project, culminating in a distinct research output.

The Children’s Activity welcome video

What we know:

The existing knowledge and evidence base

Almost two-fifths (39.6%) of Australians have been exposed to domestic violence during their childhood (Mathews et al, 2023).

2.6

million

An estimated 2.6 million Australians have witnessed violence towards their parent by a partner before the age of 15 (ABS, 2023).

36%

In 2023, a child or children were present at 36.1% of family violence incidents attended by police in Victoria (CSA, 2024).

Family violence has profound impacts on children’s health, wellbeing and development. Known harms include an increased risk of:

- mental ill-health, suicide and substance misuse (Orr et al, 2022; Gartland et al, 2021; National Mental Health Commission, 2021; Meyer et al, 2023);

- homelessness (AHRC, 2021; AIHW, 2019);

- social, behavioural and learning difficulties (Clark & Graham-Bermann, 2017; Noble-Carr et al, 2019);

- future perpetration of family violence (Campbell et al, 2020; Bland & Shallcross 2015; Campo 2015; De Maio et al, 2013; Knight 2015).

But children are often invisible in the family violence service landscape. They are the ‘forgotten’ and ‘silent’ victims (RCFV vol II, 2016: 129). Research evidence and sector insights have exposed gaps in engaging directly with children and young people who have experienced family violence to understand:

- children’s distinct and unique family violence response and recovery needs;

- how to meaningfully engage with this cohort to centralise their voices, views and experiences;

- how to embed rights-based, child-centred and trauma-informed approaches into practice and strengthen evidence about their effectiveness.

There is an increasing imperative in Australian law, policy and practice to prioritise and embed the voices and lived experiences of children and young people in the design, delivery, monitoring and evaluation of family violence support services and systems.

The National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022–2032 identifies the need to ‘[r]ecognise children and young people as victim-survivors of violence in their own right, and establish appropriate supports and services that will meet their safety and recovery needs’

(Department of Social Services, 2022: 21, 121).

Victoria’s family violence support service landscape for children

Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence identified a lack of targeted, tailored and accessible services that respond to the distinct recovery needs of children and young people. Historically, specialist family violence services have focused on the safety and wellbeing needs of women, or women and their children as a single, unified entity. Australia’s National Children’s Commissioner has highlighted the need for more ‘child-specific services’ to support children and young people who have experienced family violence ‘to recover alongside their parent or carer’ (AHRC, 2021: 23).

Children experience unique forms of family violence relevant to their individual identities and circumstances. Different forms of violence and the relationship contexts in which it occurs have traditionally been understood in the context of intimate partner violence, perpetrated by men against women, with dependent children exposed. Yet children and young people also experience violence from parents, siblings and/or other family members, which requires a nuanced, intersectional understanding of the use of power and control (YacVic, 2024: 10).

Children who experience intersecting forms of marginalisation face additional barriers to accessing effective supports, which are created and sustained by cisnormative, heteronormative, colonial, ableist and patriarchal systems of power. This includes:

- children with disability (Octoman et al, 2022)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Morgan et al, 2022)

- LGBTQIA+ children (Leonard et al, 2008; Fitz-Gibbon et al, 2023b)

- Children from migrant and refugee communities (Thoburn, Chand & Procter, 2005).

There has been progress made to recognise the distinct needs of children and young people as victim survivors of family violence in their own right following implementation of the Royal Commission’s recommendations. However, as Victoria’s Family Violence Rolling Action Plan 2020-2023 acknowledges, and the points below highlight, there is ‘still … a lot of work to do’ to translate this recognition into meaningful action (DFFH, 2020). Crucially, while several of these reforms have been designed to improve responses to, and outcomes for, all victim-survivors of family violence, there has been a limited focus on children specifically:

- Victoria’s MARAM Framework is not currently youth informed (MCM, 2021: 9, 24), although the development of children and young people-specific MARAM practice guidance and tools is in progress. Concerns have also emerged regarding the Framework’s capacity to address risk and safety for diverse communities (FVRIM, 2023: 85).

- The FVISS and the CISS do not require children’s consent to share their confidential information, which may increase their family violence risk, particularly where that information is shared with a parent who is the person using violence (FVRIM, 2023: 47).

- The Orange Door network triages service users to access specialist family violence services and broader child and family wellbeing services. Yet there are limited child-specific referral options (FVRIM, 2023; FVRIM, 2020; MCM, 2021).

- Despite increased investment into therapeutic interventions for victim-survivors of family violence, demand continues to outstrip supply and capacity, with extensive waitlists reported across Victoria (FVRIM, 2022: 48-49; FVRIM, 2020).

The evidence gap: data collection practices and underreporting

Capturing data on children and young people who are victim-survivors of family violence remains an ongoing challenge. Data deficiencies affect the ability to make evidence-informed decisions to improve service design and delivery (AIHW, 2022: 342).

Data collection practices often subsume children who are victim-survivors of family violence into the case records of their parent or guardian. Underreporting may also underlie many of the deficiencies that persist in system responses. Children and young people may:

- Be unable or reluctant to report violence perpetrated by a parent or caregiver (Eriksson et al, 2022);

- Not recognise that the behaviour constitutes family violence;

- Face barriers to reporting and/or to accessing family violence support services, due to ‘confusion, poor self-esteem and lack of accessible information’ (RCFV, 2016, vol 2: 138); concerns regarding mandatory reporting and child protection involvement; prior negative experiences with police and/or services (CCYP, 2021; YACVic, 2024); perceived stigma associated with family violence; a lack of emergency housing; and financial dependence on their parent or carer (AHRC, 2021).

Listening to children and young people’s own, unfiltered voices

The dominant conception of children in Australian society emphasises their vulnerability and dependence on adults (Dimopoulos, 2022; Varadan, 2019). Children are often treated as ‘secondary’ victims, or extensions of their parent (usually their mother) or caregiver.

This conception of children manifests in service contexts when adults underestimate children’s capacities (Toros, 2021; Moran-Ellis & Tisdall, 2019); when children’s views are not sought, listened to or heard (Duncan, 2018; Cossar, Brandon & Jordan, 2016); and through a protectionist instinct, to shield children from the ‘burden’ of decision-making and potential further trauma (Coyne & Harder, 2011).

Respecting children as victim-survivors of family violence in their own right demands an understanding of children as ‘active participant[s] in the promotion, protection and monitoring of their rights’ (CRC Committee 2006:[14]). The failure to seek, listen to and understand children’s direct, unfiltered voices about their family violence response and recovery needs exposes a significant gap in meeting those needs effectively.

What children and young people identify as important in their family violence response and recovery

Children and young people often want to share and discuss their experiences of family violence, safety and wellbeing (AHRC, 2021; Noble-Carr, Moore and McArthur, 2020; Moore et al, 2021).

Several studies that have engaged children and young people as family violence experts by experience, presented below, offer insights into what children and young people feel is important in their family violence recovery.

The overarching concern that emerges from these studies is that children and young people are inadequately or improperly engaged to understand their unique and diverse experiences. This includes recognising how experiences and support needs differ between children and adult victim-survivors, and also how support needs differ between children themselves, including within sibling groups.

These studies highlight a marked gap between what children and young people perceive to be important to their family violence response and recovery, and what existing service systems and models can provide.

Australian & International Research

The Orange Door Network: Children’s engagement pathways

The Orange Door is an integrated intake pathway for people experiencing family violence, or who need assistance with the care and wellbeing of children and young people. It seeks to assess a person’s risk and needs, conduct safety planning and facilitate crisis support. It also connects people to a range of services, including family violence services, child and family services, Aboriginal services, and services for perpetrators, which are collectively referred to as its ‘core services’.

This analysis addresses the number of cases for children aged 0 to 13 years across all The Orange Door sites by a range of characteristics recorded in the Client Relationship Manager (‘CRM’) system used across The Orange Door network. It also examines referral sources into The Orange Door and case closure reasons.

Cases for children

The Orange Door network has experienced year-on-year growth in total case numbers involving children aged 0 to 13 years between the 2017-18 and 2021-22 financial years.

Total Number of Cases for Children Aged Up to 14 Years

There has been no statistically significant change in the proportion of cases for children aged 0 to 13 years by age group between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

Case Numbers by Age Group

This growth is likely explained by the greater service capacity afforded by the staggered rollout of new The Orange Door sites and access points across Victoria (FSV, 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic may have also contributed to the increase in total case numbers for children during this period, consistent with recent research indicating an increase in adults and children reaching out to family violence service providers, including for the first time, during the pandemic (Carrington et al, 2021; Boxall et al, 2020; Pfitzner et al, 2020). Each age group has comprised approximately one-fifth of the total case numbers in each financial year.

Characteristics of children engaging with The Orange Door

Gender

Children aged 0 to 13 years who identify as male have represented a slightly greater proportion of cases in each financial year than children who identify as female

(2017-18: M=43.6%, F=40.1%; 2018-19: M=44.6%, F=42.4%; 2019-20: M=45.5%, F=42.0%; 2020-21: M=48.9%, F=45.9%, 2021-22: M=48.9%, F=46.1%)

Aboriginal Status

Children who identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander are significantly overrepresented in The Orange Door’s case numbers.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children have comprised between 8.2% (in 2017-18) and 11.2% (in 2018-19 and 2020-21) of total cases for children aged 0 to 13 years. This is disproportionately high relative to the 1.8% of the overall Victorian population, and the 5.7% of the overall Australian population, in this age group identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (ABS, 2021).

Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) status and disability status

Total case numbers for children aged 0 to 13 years by CALD status and disability status demonstrate a significant number of ‘unknown’ cases, particularly between the 2017-18 and 2020-21 financial years.

During this period, the proportion of ‘unknown’ cases was between 82.9% and 84.5% for CALD status, and between 88.0% and 92.2% for disability status.

The proportion of ‘unknown’ cases reduced markedly in the 2021-22 financial year , to 62.6% for CALD status and to 71.1% for disability status.

This decrease may reflect The Orange Door’s ongoing efforts to improve data collection about language spoken at home, disability status and country of birth, coupled with enhancements to the CRM to focus on ‘increasing the quality and quantity of data collection on diverse communities with an emphasis on CALD and LGBTIQA+ communities and clients with a disability’ (FSV, 2023).

Children’s pathways into The Orange Door

Most common pathways into The Orange Door by referral source

1. Police reports

Referrals come directly from Victoria Police when there has been a reported incident of family violence, known as an ‘L17’.

2. Other professionals

Including registered community organisations that provide family services tailored to children and young people as part of their service offerings.

3. Child Protection

4. Self-referrals

Clients make direct contact with The Orange Door themselves. However, the data do not distinguish between a self-referral made by a child and a self-referral made by the child’s parent.

Data limitations:

- Limitations in linking case data and referral data mean that the total number of referrals for children does not match the total number of cases for each financial year.

- Some cases are linked to multiple referrals from the same day, most of which are police referrals. Where this has occurred, the data provided is for only one referral source.

- A referral can be for an individual or a group, such as a family. While a separate case is subsequently created for each individual in a referral, referral sources related to a child’s case are often the referral source that is carried over from a parent’s case.

- The number or proportion of cases where the case closure reason recorded for a child’s case has been carried over from a parent's case (for example, when a parent declines a service) is unknown. The data therefore offer little insight into whether and how children’s own, distinct family violence response and recovery needs are being addressed effectively.

Children’s pathways through

The Orange Door

Pathways through The Orange Door for children are based on five key case closure reasons

- Engagement with the service system

The Orange Door connected the client with the service system for further support, and may have also provided other services as part of an interim response.

- Needs met by The Orange Door

The client received a service delivered directly by The Orange Door (e.g. a targeted or brief intervention such as brokerage), or the client may have already been engaged with support services and The Orange Door did not actively connect the client with the service system.

- Client was unable to be contacted

- Client declined or disengaged

(1) the client declines an offer of any service from The Orange Door; or (2) the client initially engages and then advises that they no longer want support; or (3) the client initially engages but then relocates and does not agree to be transferred to their new catchment area; or (4) the client initially engages and then is no longer contactable (after the required contact attempts are made). A client may disengage at any point in the service continuum.

- ‘Other’

Case closure reasons with small proportions, including where the service is no longer required, the client has transferred to another area, contact with the service is deemed unsafe or inappropriate, a case has been created in error, or the client is deceased.

Engagement with the service system has been the most common pathway through of The Orange Door network for children. This client outcome reflects the continuing importance of closely integrating The Orange Door network with the broader family violence support service network (PwC, 2018; VAGO, 2020).

‘Client declined or disengaged’ has experienced the clearest and most consistent growth amongst the five client outcomes between 2017-18 and 2021-22, from 10.6% of total cases when The Orange Door commenced operation to 23% of total cases by the fourth quarter of 2012-22.

Practitioner Insights

This section presents the findings of a survey of 320 practitioners in Victoria who provide support services to children aged up to 13 years who have experienced family violence.

Practitioner and service characteristics

Do you work for a specialist family violence service?

Almost one third (101/319 = 31.7%) of practitioners worked for a specialist family violence service.

For non-specialist family violence practitioners who selected ‘Other’ and described the nature of their service, the most common descriptors were:

- family services (n=21);

- family preservation and reunification (n=5);

- family and parenting support, including parenting programs (n=4);

- services related to the DFFH, including child protection and child safety (n=4);

- Aboriginal child and family services (n=3);

- housing (n=2);

- family-based care, such as foster care (n=2);

- victim support (n=2);

- therapeutic support (n=2);

- school counselling (n=1);

- alcohol and other drugs (n=1);

- mental health (n=1);

- bilingual support (n=1);

- family contact services (n=1).

Over half (201/313 = 64.22%) of practitioners worked mainly in metropolitan Melbourne.

Hume Moreland

14 (4.79%)

North Eastern Melbourne 33 (10.54%)

Outer Eastern Melbourne 32 (10.22%)

Inner Eastern Melbourne

28 (8.95%)

Southern Melbourne

31 (9.9%)

Bayside Peninsula

63 (20.13%)

A majority of practitioners (195/318 = 61.3%) indicated that their service supported children aged up to 13 years who have experienced family violence ‘very often’.

Very often (support children 75-99% of the time)

Sometimes (support children 50-74% of the time)

Our only cohort (support children 100% of the time)

Rarely (support children less than 50% of the time)

Specialised programs for children

Overall, 38.4% (123/320) of practitioners indicated that their service had programs specifically designed for children aged up to 13 years who have experienced family violence.

These programs included individual counselling, group work programs, dyadic therapeutic programs, art therapy, play therapy, fun buddies and programs such as Beyond the Violence, Strength2Strengh, Pathways to Resilience, and Yarning About Family.

Practitioners who work for a specialist family violence service were more than twice as likely to indicate that their service provided child-specific programs than practitioners who do not work for such a service.

Practitioners who responded ‘Yes’ to the question, ‘Does your service provide any programs specifically designed for children (aged 0 to 13 years) who have experienced family violence?’ | |

All practitioners | 38.4% |

Work for a specialist family violence service | 61.4% |

Do not work for a specialist family violence service | 27.9% |

Work for an ‘other’ service | 26.4% |

Training to work with children

Just over half of practitioners (173/318 = 54.4%) had undertaken internal, external or accredited training within the last 12 months to work with children aged up to 13 years who have experienced family violence.

Practitioners commonly referred to MARAM training, organisations such as Safe & Together, the Australian Childhood Foundation, Anglicare, Emerging Minds, Blue Knot and Berry Street.

Within the last 12 months, have you undertaken any internal, external or accredited training to work with children (aged 0 to 13 years) who have experienced family violence?

Seeking feedback from children

Less than half of practitioners (144/315 = 45.7%) indicated that their service asks children aged up to 13 years for feedback about their service experience.

Does your service specifically ask children (aged 0 to 13 years) for feedback about their experience of your service?

Most common methods for collecting feedback from children:

- verbal process (n=110);

- end of support period survey (n=74);

- online feedback form (n=50);

- complaints procedure (n=41).

Elaborating on these feedback methods, practitioners referred to:

- Conversations and informal face-to-face chats;

- Inviting the child to draw pictures or write letters about their experience;

- Text message, email or telephone feedback;

- Using stickers and visual charts, smile feedback scales, child-specific scaling tools, diagrams or pictorial methods;

- Games or play;

- An anonymous suggestion box;

- Group sessions that collect responses via whiteboards or butcher’s paper;

- ‘Easy to read’ or ‘child-friendly’ online or paper surveys and questionnaires.

- The Australian Childhood Foundation’s Action Feedback Kit.

A number of practitioners indicated that feedback from children was provided through an adult, such as the child’s parent or carer or case worker:

They can voice their feedback to their parents, who can then pass on the feedback to me … [Practitioner 269]

Through their carers and through their case manager [Practitioner 191]

Some practitioners identified non-verbal or play-based methods to facilitate feedback through practitioner observations and creating a safe space for children to express themselves:

Children can provide feedback by monitoring their interaction with parent and workers. Children often display feedback through their actions and responses to activities provided for them. The environment has been designed to allow the child to explore freely or with guidance. The child often engages in their own interest which then gives the workers the opportunity to observe and gain feedback on their likes and dislikes. After children have settled in, guided play is provided with supported staff and parent that then allows parent and worker to observe child's feedback [Practitioner 157]

Several responses suggested that the onus is placed on the child to proactively engage to offer feedback:

Children are … told they can provide feedback to their counsellor or via their parent/carer any time [Practitioner 237]

Children are encouraged to provide feedback throughout therapeutic interventions verbally, and are able to engage in a complaints process where desired [Practitioner 162]

For a small number of practitioners, the child’s age was perceived as a barrier, or the child’s ‘age and stage’ determined whether particular feedback opportunities would be provided:

Depending on the age of the child. Verbal and preverbal responses are collected [Practitioner 253]

We only work with children up to the age of 4

[Practitioner 152]

When at an appropriate age and stage, young people fill out self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaires, which reflect their feelings around the service and their progress [Practitioner 162]

For many practitioners, feedback from children was sought only at the conclusion of their service engagement, via a ‘closure session’ or end of service evaluation form or annual survey. Actively seeking and encouraging ongoing feedback from children and young people throughout their service engagement was not common.

Some practitioners noted that feedback forms were provided to the family (that is, the adult members) engaging with their service, not specifically to the child:

During appointments with the whole family, children might be asked to reflect on any changes they have noticed in family life since service delivery began. Risk assessment would be made before asking children to speak about this, particularly if [person using violence] is present [Practitioner 139]

Feedback form provided to family at the end of service. Complaints form provided at commencement of service to family. Upon reflection these should both be provided specifically to the young person as well [Practitioner 319]

Nine practitioners acknowledged seeking feedback from, and listening to, children about their experience of services as a service limitation:

While we seek to support children, we currently don't run groups aimed at their age group, and feedback mechanisms are more adult friendly. Adolescents are a huge service gap [Practitioner 22]

We rarely hear back about the children's experiences unless the children are connected to their own worker (such as a counsellor or a teacher) and we are actively seeking feedback from them. We often don't hear from the children away from their parents so we rely on observation, child protection reports and the parents’ opinion on what the children want and need

[Practitioner 144]

Features of effective service responses

Practitioners were asked to reflect on what their service does well to support children aged up to 13 years who have experienced family violence.

Collaboration and Referrals

The feature most commonly cited by practitioners was the strength of their service’s collaboration and referral networks:

We partner with services who have specialised [family violence] knowledge either through direct referrals or secondary consults [Practitioner 66]

We will work holistically with other services/schools that are supporting the children aged 0 - 13 years old

[Practitioner 106]

Referrals to other supports. Building rapport, assisting with navigating the legal system [Practitioner 101]

Trauma-informed Practice

The use of trauma-informed processes and perspectives was also reflected on positively by 34 practitioners:

We are incredibly good at having a trauma-informed developmental lens around children's experiences to help them heal from their experiences of trauma [Practitioner 130]

We're a specific trauma-informed therapeutic service: gathering voice of the child; systems work to highlight child's experience/voice; undertaking individual, family and dyadic work with parent/child, to restore the relationship/attachment after the ruptures [family violence] causes; write therapeutic narratives/lifestory representations of their experiences with them; trauma processing, etc [Practitioner 257]

Safe Spaces

Some practitioners reflected that their service provides a safe space for children to talk about sensitive issues that they might not otherwise feel comfortable sharing or discussing, while others positively described their service’s risk assessment and safety planning:

Offering a safe space for children to connect with others and find new ways of managing any ‘big’ feelings [Practitioner 303]

Our service works directly with children and offers a safe space for children to safety plan and speak about their experiences with family violence

[Practitioner 88]

Child-centred Practice

There were 76 references broadly to child-centric approaches, including services prioritising the needs of children and conceiving them as victim-survivors in their own right, and advocating for children’s voices to be heard and centralised:

Ongoing understanding and reflection on how childhood experiences of family violence impacts the development and future relationships of adolescents, and that young people are victim-survivors in their own right [Practitioner 313]

We usually make sure that children know that their voice is very important to us and want their input, making time for a private space that they feel comfortable sharing [Practitioner 134]

While 41 practitioners identified listening to children’s voices as something that their service does well, one practitioner noted that this can vary from practitioner to practitioner:

It is dependent on the worker. Some workers are really good at placing the child at the center of the work but others focus on the parent. My service has lots of tick box forms to ‘capture the voice’ of the child but these are often done at closure and in a meaningless way [Practitioner 170]

Holistic Support for Families

Another commonly identified strength was the provision of holistic support to parents, carers and families, in addition to supporting children themselves. Twelve practitioners expressly mentioned that they are skilled at educating parents on the effects of family violence on children:

Working with parents to build their capacity and understanding of their children's needs and educating them about the impact of family violence, helping parents/carers be present, responsive and compassionate to children's needs

[Practitioner 83]

Five practitioners noted the strengths of dyadic therapy to rebuild or strengthen relationships between parents and children, after what one participant described as the ‘ruptures’ that family violence causes:

Our parenting support program has a play component that supports and encourages connection between mother and child. The program uses play as a way to rebuild their relationships and create positive memories. We also run therapeutic sessions, based on the individual needs of the clients that then supports the children through their parents

[Practitioner 157]

Barriers to effectively supporting children

Practitioners were asked to identify the barriers they face in effectively working with children who have experienced family violence.

Insufficient resources, time and experience

Over half of practitioners (106/195 = 54.5%) identified insufficient training, resources and time as barriers to supporting children who have experienced family violence.

Of this subset, over one quarter (30/106 = 28.3%) referred generally to system-wide resourcing and funding concerns:

Inability to respond in a timely way due to high service demand, insufficient access to suitable accommodation in crisis, shortage of staff in child protection - too many referrals re-directed to The Orange Door where there is significant risk to the immediate safety and long-term wellbeing of children [Practitioner 63]

Funding constraints. Services and families are keen to participate, demand is high, however, there is often a lack of funding to support the activities of this type of group work [Practitioner 253]

Training and experience emerged as another significant barrier. Almost half (94/206 = 45.6%) of practitioners considered that they lacked training or felt ill-equipped to adequately support children due to a lack of experience or confidence. Practitioners explained:

I have been in the therapeutic field for 5 years, supporting children who have experienced family violence and I have had to fund all of my own training. There is a significant gap in training available to staff … in this sector [Practitioner 161]

Having access to specific training for working with trauma related to family violence and children, often not in our budget range. We don't employ child therapists, it’s expected all counsellors work with adults and children but often they only have minimal training [Practitioner 22]

Being fearful of retraumatising them and not being trained well enough to interview [Practitioner 85]

One quarter (27/106 = 25.6%) of this subset of practitioners also specified their service time as barrier:

Support period is often too short to support the crisis stage, support the family to "leave" the [family violence] and then also support the emotional and mental health of both parents and child. Often, our support period is so brief that we cannot cover all bases adequately and access to services in our area is very challenging [Practitioner 216]

We all understand that we need to support children as well as adult victims. But in practice it is different, the worker sometimes needs to close a case in three months and report what goals were achieved. [It] seems like systems focus on quantity, not quality [Practitioner 47]

Our service is short term (3-6 months) and so we have limited time as practitioners to develop rapport and work therapeutically with children who have experienced violence [Practitioner 88]

We are funded for 40 hours of support. Not enough. A child who is in the process of healing after [family violence] needs a minimum of twelve months of ongoing support with a trusted practitioner who can work with the child and Mum [Practitioner 229]

Some practitioners expressed the view that MARAM was not being used optimally, or that they needed further training to better understand how to use it:

Better understanding of Child Protection role regarding MARAM and hearing voice of the child [Practitioner 148]

More education re: child/adolescent MARAM and implementation into services [Practitioner 203]

Lack of specialised services for children

Forty-one practitioners identified a lack of appropriate, child-specific referral options or programs – such as play therapy, art therapy, relational based family therapy, group programs, counselling and educational support – or difficulties accessing these services due to cost or long waitlists, to be a barrier to effectively supporting children who have experienced family violence:

There are limited services and long wait times for children to engage with services to address the trauma they have experienced … There are no services available for young people who go on to use violence in the home due to the example that has been set by a violent parent [Practitioner 177]

More opportunities for children to work in groups, as women and men do. Both adult groups have been found to be beneficial, peers can relate and challenge in ways that professionals cannot do [Practitioner 253]

Better access to specialist services in small rural regions … [Practitioner 170]

A related concern for 14 practitioners was a lack of access to children, who commented that standard ‘business’ hours largely overlapped with the standard school day:

For some practitioners, specialised programs and services are especially lacking for children with diverse needs, including children with disability and from culturally and racially marginalised communities:

Targeted services for children who have disabilities to help them to understand and process the trauma of [family violence] [Practitioner 207]

Greater funding and variety of programs (for CALD clients and clients with disability)

[Practitioner 243]

Six practitioners identified an age-based service gap for children with respect to programs and counselling services, with one noting:

A program specifically for that age bracket, it seems to be missed. There are programs for over 12 years old usually, but none below this age. Having programs or groups for the younger children would be a great advantage, as this is the time they start to move off the right path. It could be ideal in helping them [Practitioner 57]

We don't get to meet regularly with children as they will be at school during our home visits. [Practitioner 106]

Often limited hours that we can see the children e.g. office hours are 8.30am to 5pm but children are often at school for extensive amounts of this time and means they often have to miss school to attend sessions [Practitioner 211]

Barriers posed by parents/carers and children themselves

For 41% (80/195) of practitioners, the willingness and ability of children and/or their parent/carer to engage with the service affected their ability to provide effective supports.

Of these practitioners, over two-fifths (33/80 = 41.3%) reported that parents were sometimes unwilling or unable to consistently and meaningfully engage their children with the support offered:

Many practitioners also referenced a lack of parental understanding or acknowledgment of family violence and its effects upon children:

Parents/care givers lacking insight or not wanting their child to get support and putting it down to 'behaviours' or 'they aren't impacted’ [Practitioner 204]

Parents denying any family violence, means that the child sometimes does not recognise it either. Some children do not have the words to talk about it or even understand it as it is 'normal' for them [Practitioner 57]

A small but notable proportion (16/195 = 8.02%) of practitioners referred to children lacking trust or being fearful or uncomfortable about engaging with the service:

Children may feel afraid or distrustful of adults and may feel closed off and inaccessible as a result of experiences of violence or abuse [Practitioner 17]

[C]hildren are often guarded and fearful of being removed from their parents. This can hinder them being open to discussing fears and experiences

[Practitioner 159]

Engagement with children, sometimes blocked by parents or by reluctance to speak to services [Practitioner 136]

Parental mental health results in difficulty engaging in our service at times and high cancellation rates

[Practitioner 238]

Some practitioners noted that people using violence can be a significant barrier, including where parental consent is required for the child to access support, or by putting the child at risk through ongoing contact:

Consent from the perpetrator if they are having contact with the child is a significant barrier, the perpetrator will often sabotage the therapy process as a way of control [Practitioner 133]

[C]urrently a big number of children being refused service due to unsafe parent holding the consent to engage with a service or therapeutic work can't be provided due to ongoing safety concerns related to child contact with person using violence [Practitioner 25]

Barriers posed by the family law system

The family law court acts as a significant barrier - perpetrators often engage in financial systems abuse and counselling for children and mothers whilst going through family law court is often discouraged by their lawyers due to risk of documents being requested [Practitioner 133]

Ten practitioners raised family law system processes as a barrier. They identified delays, parenting orders requiring children to spend time with the person using violence, and consent required from both parents for the child to access support services, as further enabling abuse or manipulation:

[Court] decisions around ongoing contact with perpetrators that lack holding them accountable for the harm they have done to the non-offending parent's parenting capacity, and therefore their children. If the parent isn't a primary carer court does not always insist they engage in programs, before getting contact. After time passes, in some cases court can overlook the severity of violence a perpetrator caused, and place child with perpetrator of intimate partner violence, if non-offending parent can no longer undertake care [Practitioner 257]

Service system reforms needed

Practitioners were asked to reflect on reforms required to the service system to ensure that children and young people are supported as victim-survivors of family violence in their own right.

Increased funding and resources

Almost half (84/169 = 49.7%) of practitioners suggested an increase in funding and resources for the family violence sector.

Practitioners sought an increase to the size of the workforce and more funding to improve the quality and timeliness of service responses:

More funding/resources for more on the ground family support workers to keep up with the demand/complexities (intersectionality of the [family violence], mental health and [alcohol and other drugs] concerns, intergenerational trauma) of cases that are coming through from The Orange Door. Currently there is pressure to close cases to pick up more cases/or holding higher caseloads impacting on quality of service provided to victim/survivors/children [Practitioner 125]

More staff, more hours, more money [Practitioner 129]

Quicker distribution of brokerage to help them start over or access emergency accommodation whilst homeless [Practitioner 46]

More family violence case management funding and linked therapeutic programs directly for children, better accommodation options for families, more staff on the ground in all areas [Practitioner 63]

Reforms to the family law system

The family law system was identified as an area ripe for reform by 16% (27/169) of practitioners, who commented upon how the issue of family violence is approached when making parenting orders following parental separation:

Inquiry into family law proceedings that continually allow perpetrators to have contact with their children despite high levels of family violence occurring. There is an inconsistency with decision making and bias with report writers completing child impact reports across all matters [Practitioner 222]

Significant delays in the court system place great risk. If a mother tries to stop their children from going due to [family violence], then they are in breach [of parenting orders], and this goes against the mother trying to protect their child [Practitioner 204]

A commonly-suggested reform in this context was to listen to children’s voices and to recognise them as a key stakeholder in family law matters and related processes:

[C]hildren to have a greater voice when it comes to parenting agreements and giving them greater rights. Many children I've worked with have expressed not wanting to see the parent who has used to violence due to fears, or ongoing abuse. The … courts have not responded, and the child is forced to continue to see this parent. The children have been subjected to ongoing violence which may on paper not be deemed 'appropriate for police intervention i.e withholding food, psychological abuse and manipulation, using heating and cooling as means of control [Practitioner 204]

Holding perpetrators more accountable and allowing a child’s voice to be considered when an IVO matter is being applied for or during family court hearing [Practitioner 160]

Reforms to police processes for protection orders

Some practitioners also suggested improvements to how Victoria Police issue family violence intervention orders:

Police need to ensure that all children are listed as protected persons when applying for IVOs. Ensure that children are listed on all family violence police reports [Practitioner 121]

Reforms to Victoria police - often issuing full [intervention orders] to young people using violence leads to further exclusion and isolation and further perpetuates the cycle [Practitioner 120]

Specialised programs for children

Almost one-fifth (30/169 = 17.6%) of practitioners referred to increasing the emphasis on children in the system, particularly through access to specialised, tailored services:

I would advocate for immediate crisis and long-term child specific counselling or therapeutic services that allow children to safely understand their experiences and complex feelings about their family members and relationships [Practitioner 53]

[M]ore range of programs that can support the children where they are at (e.g. if it's not the time for therapeutic counselling or clinic based support, could there be some level of outreach support or in-school support provided?) [Practitioner 114]

Improved collaboration, information-sharing and community awareness

A small proportion (12/169 = 7.1%) of practitioners suggested improved collaboration and information-sharing across the service system:

More open collaboration between services; schools, Child Protection, police, medical and family services [Practitioner 103]

Greater collaboration between agencies and department regarding the importance of responding appropriately to children who have experienced family violence [Practitioner 212]

The importance of education and enhanced community awareness of family violence and its impacts on children was also highlighted, particularly as a preventive strategy. Some practitioners suggested that all professionals who work with children beyond the family violence context, such as in school and early childhood settings, should also receive family violence training:

Supporting child care, kindergarten, primary schools with family violence identification as they can be the first point of contact for young children [Practitioner 121]

Mandated professional development regarding child mental health and around trauma informed care in all childhood settings including kinder, primary, early childhood care and playgroups. This would enhance all practitioners’ awareness and knowledge of childhood mental health issues and trauma informed care approaches to support children impacted by family violence [Practitioner 256]

Notably, however, one practitioner suggested that the sector is suffering from ‘reform fatigue’:

The sector is experiencing reform-fatigue in the family violence space. My team are still grappling with the changes that MARAM and the FVISS and CISS have introduced [Practitioner 104]

Children’s Needs and Experiences

This section presents the findings of an online, interactive Children’s Activity completed by 23 children and young people in Victoria with lived experience of family violence in the research project. It presents the findings regarding participants’ family violence response and recovery needs, followed by their experiences of family violence support services in Victoria. Finally, children and young people’s suggestions for improving Victoria’s family violence service system are discussed.

About the children and young people

The 23 children and young people who participated in the Children’s Activity were between 7 and 25 years old.

How old are you?

Almost half of participants (47.8%, n=11) identified as female, just over one third (34.8%, n=8) identified as male, and 13% (n=3) identified as non-binary. One participant did not disclose their gender identity. Only one participant (4.3%, n=1) identified as Aboriginal.

Only one participant (4.3%, n=1) indicated that they ‘sometimes speak English and sometimes speak another language at home’.

How do you identify?

Are you Aboriginal or Torres Straight Islander?

How often do you speak English in the home you live in most or all of the time?

Over half of the children and young people (13/23 = 56.5%) disclosed that they have a disability, chronic health condition or mental health condition. Of the 13 participants who disclosed a disability or health condition, over half (53.8%) were aged 16 to 25 years, almost two-fifths (38.5%) were aged 11 to 15 years, while one was below 10 years of age (7.7%).

Do you have a disability, chronic health condition, or mental health condition?

The majority of participants lived with their mother (52.2%, n=12), or with their mother in addition to other family members, including sibling(s) (21.7%, n=5), or with both mother and father (or stepfather) (17.4%, n=4). One participant lived with their partner and one participant lived with their housemate.

Who do you live with most or all of the time?

Almost half of these children (6/13 = 46.2%) listed two or more co-occurring disabilities or conditions:

- anxiety (n=6), including chronic anxiety and trauma anxiety;

- depression (n=4);

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n=3), including chronic PTSD;

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (n=2);

- borderline personality disorder (BPD) (n=1);

- autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (n=1);

- polycystic kidney disease (n=1).

All participants who identified as non-binary (n=3, 100%) disclosed that they had a disability or health condition; as did half of the male participants (4/8 = 50%) and over half of the female participants (6/11 = 54.5%).

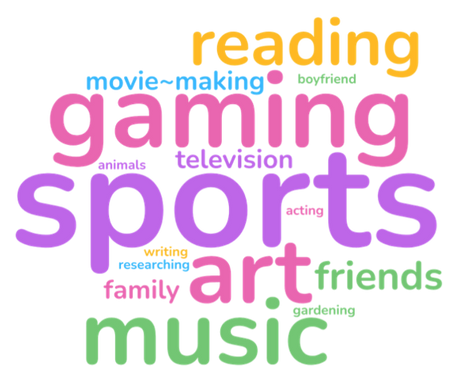

The Children’s Activity also asked participants what they like to do in their spare time.

Word cloud of most popular responses

Submited artwork from a participant

I like to play with animals! I am a big animal lover and I love to listen to music on walks [Anita , 17]

Playing Roblox, doing my hobbies like gymnastics, spending time with mummy [Angelica, 10]

Editing videos, playing video games and watching anime [Xavier, 10]

Reading, music, art, crotchet, play games, see friends and boyfriend [Gabby, 18]

I am constantly painting and creating art to express my inner urge for creation – it helps me to calm down and feel good [Casey, 12]

What children and young people need to feel safe and well

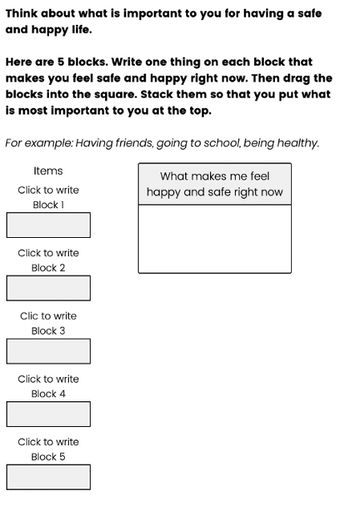

Participants were asked to reflect on and list five things that currently make them feel safe and happy in their life, and five things they need to feel safer and happier. The questions from the survey is extracted below.

Explore the particpants responses to both questions with the word clouds below. Drag the bar in the middle to the left and right.

Relationships and connection

Relationships and connection with family, friends, a partner or pets, were identified by all children and young people as something that made them feel safe and happy in the present.

Participants most commonly named:

- Friends or ‘besties’ (77.3%, n=17)

- Pets (dogs and cats) (54.5%, n=12)

- Mother (50%, n=11)

- Family generally (27.3%, n=6)

- Siblings (18.2%, n=4)

- Grandparents (9.1%, n=2)

- Boyfriends (9.1%, n=2)

16 participants listed a family member, friend or partner as most important for their current safety and happiness: and half of these participants (n=8) specified their mother. A further five participants referred to their family, including spending time with and dining with them, and their family being healthy.

Interpersonal relationships were also identified by over three-quarters of children and young people (18/23 = 78.3%) as something they required to feel safer and happier. Some participants named a particular person or relationship, such as a parent, sibling, friend, boyfriend. Others commented on the need for improvements in the nature and duration of, and overarching conditions enabling, these relationships: ‘Quality time with family’ [Anita, 17], ‘Spend more time with my mum’ [Angelica, 10], and ‘Just and fair circumstances for me and mum’ [Casey, 12].

Also prominent was the need for positive and stable relationships, which for some participants could be found beyond their current friends and family:

If I had other safe adults that felt just as good as my mother [Sam, 8]

Finding more friends that I relate to and trust. Be around people that I trust, like mum’s family [Angelica, 10]

Casey, aged 12, expressed a need for ‘agreement between my parents … Honesty and transparency with my parents’. A desire for better parent-child communication and agreement between a child’s parents is reflected in research with children and young people in separated families (Carson et al, 2018). Seven-year-old Amara poignantly listed one word as the most important thing for her to feel safer and happier: ‘Love’.

Physical security

Over one third (8/22 = 36.4%) of children and young people referred to a type of security or safety mechanism attached to their living situation as something that made them feel safe and happy in the present.

These included ‘living in a gated community’ [Sam, 8], a ‘pet guard dog’ [Amara, 7], ‘new locks’ [Anita, 17], a ‘phone with tracking … security cameras’ [Darius, 12], and ‘locking the front door’ [Isabelle, 20]. For [Oliver, 15], the person using violence complying with a family violence intervention order (FVIO) helped them to feel safe and happy.

Two participants listed ‘no police’ [Molly, 11] or ‘being away from police’ [Oliver, 15] as important to their present feelings of safety and happiness.

Half of participants (11/22 = 50%) identified home, their bedroom or an aspect of their home environment as important to their current safety and happiness.

While the absence of police was identified as important for two participants’ current feelings of safety and happiness, two different participants described protections afforded by police as something they sought to feel happier and safer, including ‘police check-ins’ [Malik, 12], and ‘police red flagged house’ [Jenny, 17].

For some, ‘home’ was connected to safety and being away from their perpetrator, while for others, it was a place of comfort, privacy and stability: ‘Being safe at home and away from him’ [Molly, 11]; ‘Having a home in a safe community’ [Sam, 8]; ‘Stability with where we are living. Certainty in my life’ [Oliver, 15].

A need for greater physical safety and security was identified by over half of participants to feel safer and happier (13/23 = 56.5%).

Some were again physical items, including ‘Cameras around the house’ [Arthur, 15], ‘Locks on doors. Lights at night’ [Jamie, 21] and ‘Phone with GPS’ [Darius, 12]. Others revealed children and young people’s deep feelings of fear and a desire to relocate, or to have ‘dangerous’ people dealt with appropriately:

For my abuser to be locked away. Having a different car. Moving house [Hannah, 16]

Moving house again so dad doesn't know and can't find us again [Tariq, 11]

Housing Stability

The need for changes to and/or stability in their living situation also emerged as an unmet need for almost half of participants

(11/23 = 47.8%).

This manifested in wanting to remain with one parent or in the same house, to move to a new house, or to live with their partner: ‘If I could stay with my mother all of the time’ [Sam, 8]; ‘Living in one house. Living without fear’ [Darren, 13]; ‘Living with my boyfriend. Moving homes’ [Isabelle, 20]. Rowena, aged 25, alluded to being homeless, seeking ‘a roof over my head’.

Health and wellbeing

Hobbies

A hobby or activity was something that made half of participants (11/22 = 50%) presently feel safe and happy. These hobbies included musical theatre, games, music, playing sports, writing poetry, reading, drawing and art.

Almost one third of participants (7/23 = 30.4%) listed various hobbies and activities as significant for their improved safety and wellbeing, including drawing, sports, access to art classes and supplies, playing games, going for drives, and ‘a lead in the [theatre] production next year’ [Zahra, 16].

Five participants described health and wellbeing-related activities to be crucial to them feeling safe and well in the present. These included ‘nourishing my body and eating well … sleeping well … being active’ [Gabby, 18], ‘eating’ [Kevin, 16], ‘walking’ [Jamie, 21], and ‘being healthy’ [Hannah, 16].

Children and young people co-analysing the data with the research team highlighted that healthy eating is not necessarily, or exclusively, related to a focus on improved health and wellbeing. It may also expose a child’s specific experiences of abuse and/or neglect, such as an irregularity of meals due to financially abusive or controlling behaviours (Johnson et al, 2022; Morais et al, 2024; McKay and Bennet, 2023; Laurenzi et al, 2020).

A higher proportion of participants (10/23 = 43.5%) identified the need to improve their health and wellbeing in order to feel safer and happier.

For some, the focus was on their physical health: ‘Get enough sleep. Get outside. Eat a balanced diet’ [Gabby, 18]; ‘Eat healthier’ [Anita, 17]. Others referred to strategies for improving their mental and emotional health and wellbeing, including ‘calm self when exposed to triggers’ [Gabby, 18], ‘a formal BPD diagnosis and a psychiatrist’ [Zahra, 16], ‘regular therapy’ [Hannah, 16] and ‘less stress’ [Darren, 13].

For two participants, it was not only their own health and wellbeing that was important to their improved safety and wellbeing, but also that of their family members.

Oliver, aged 15, wanted ‘Mum to be healthy’ and Isabelle, aged 20, commented on ‘My family being happy’. These responses are consistent with research findings that children who are victim-survivors of family violence may feel anxiety for others, particularly their mother and siblings. They may also take on the burden of adult tasks and responsibilities or a ‘protector’ role in the family, including intuitively putting in place measures to keep their family members safe (DVSM, 2017: 11; Fitz-Gibbon et al, 2023).

Physical possessions and comfort

Six participants identified specific physical possessions from which they derive comfort or pleasure in their current circumstances of feeling safe and well, including their bed sheets, mobile phone, drawing book, teddies, books and comfortable clothes. These items may offer a level of psychological safety for children who have experienced family violence, representing stability and comfort during a period of uncertainty (Fehlberg et al, 2018). Three participants described specific items that would offer them a sense of comfort and refuge and enable them to feel safer and happier: ‘Eating vanilla wafers. Sleeping with a heat pack’ [Lisa, 11]; ‘Oversized clothes’ [Jamie, 21]; and ‘My phone’ [Tariq, 11].

Financial security

The need for greater financial security was also important for over one quarter of participants to feel safer and happier in their lives (6/23 = 26/1%).

Two participants referred to employment for themselves and/or their parent: ‘Getting a job’ [Hannah, 16] and ‘Mum having a job’ [Oliver, 15]. One participant referred generally to ‘money’, and three specifically identified ‘food’ or ‘food and supplies’. Sam, aged 8, expressly linked the personal importance of being ‘rich’ with greater stability and safety in their living situation:

Being rich so that we can buy a house and staying with my Mum. Being rich so that we can buy a house so that we never have to move. Being rich so that we can buy a house.

Support networks

The need for additional, tailored support – including for mental health and schooling – also emerged strongly as an unmet need for over one quarter of participants (6/23 = 26.1%).

Children and young people shared that they sought ‘Help with school attendance’ [Zahra, 16], ‘people surrounding me who support me‘ [Darren, 13], ‘having mental health support’ [Anita, 17] and ‘regular therapy’ [Hannah, 16].

Autonomy and choice

A small but notable number of participants (4/23 = 17.4%) sought greater autonomy and support to enable them to live their life in accordance with their own views, wishes and needs. They identified increased agency in their schooling, more options to engage with peers, and more freedom to make their own decisions:

Going to the choice of school I want that makes me feel safe [Charlie, 12]

People supporting me with my choices. Have more places to go to do free activities with other kids [Angelica, 10]

Family violence support services accessed by children and young people

The age of participants when they accessed support for family violence ranged from under one year to 16 years.

Participants were also asked to share, ‘When you got that help’. The framing of this question led to several different interpretations. The trusted adult of one participant noted: ‘This adult is unsure of the question. Is this asking what year we got help? Or is this a prompt? We are a neuro-diverse household that requires precise instructions.’

Eight participants provided the year they accessed support, which ranged from 2016 to 2023. Five participants stated their age, while another listed their school years. Six participants described the situation that led to them accessing family violence support, with five of these participants identifying their or their sibling’s father as the person using violence:

Participants identified a total of 21 different services from which they received support. Twelve participants listed more than one service. The support services included specialist family violence, health, housing and homelessness, legal, police, child and family, child protection, and counselling and mental health. The most commonly accessed support services were The Orange Door (n=5), police (n=5), and counselling (n=4).

My little brother’s dad put my mum in hospital [Malik, 12]

When my dad gave me a black eye and put my mum in hospital by strangling her [Darius, 12]

When I was 11 and my dad put me and mum in hospital [Arthur, 15]

Because dad found out where we lived and tried to break in and hurt us again [Tariq, 11]

My dad still caused problems [Amara, 7]

During legal proceedings around custody from a parent with FVIO against them [Charlie, 12]

Children and young people’s experiences of family violence support services

The Children’s Activity presented participants with 15 prompts that enabled them to share their experiences of family violence support services they had accessed in Victoria. Each prompt had three response options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Sort of’. Participants could select more than one option for each prompt. This occurred for 11 out of 15 prompts, although all 11 multiple responses were provided by just two participants, both of whom had accessed multiple services. Each prompt was accompanied by an open text box that enabled participants to elaborate on their response.

Feeling welcome

The majority of responses (62.5%, n=15) indicated children and young people felt welcomed by the service.

Oliver, aged 15, added, ‘It was a bit tick the box’. Notably, two children and young people described overall positive experiences:

They were very friendly [Xavier, 10]

They were all very helpful during a really scary and confusing time [Hannah, 16]

They welcomed me and go to know me

Cultural awareness

Participants were asked whether the service understood their culture and where they came from. While over three quarters of responses (76.2%, n=16) were positive, this finding must be contextualised by the low uptake of the Children’s Activity by children from culturally and racially marginalised communities. Two participants did not respond to this statement because it was ‘not really applicable to me’ [Oliver, 15] and ‘I don’t think I have a culture’ [Jamie, 21].

Molly, aged 11, who identified as Aboriginal, described significant limitations in the ability of services to meet her cultural needs, including due to their failure to see her as separate to her mother:

They understood my culture and where I come from

We just want to be safe. We don’t want police and child protection or stupid people getting clap sticks when they find out you’re Aboriginal when your mob don’t even use clap sticks or do dot painting. They think we are extensions of our mums but we aren’t. She’s not Nyoongar but I am.

Respect for gender identity

The vast majority of responses (90.9%, n=20) indicated participants considered the service respected their gender identity.

Although Molly, aged 11, described gender stereotypes as marring her service experience:

I’m a girl but that doesn’t mean I like girly stuff so trying to get me to talk by talking about makeup and stuff like that just made me mad.

They respected my gender and how I identify

Accommodating disability needs

Participants were asked whether the service understood what they needed because of their disability. While nine participants (39.1%) indicated that they do not have a disability, just over half of the remaining responses to this prompt were positive (n=8, 57.1%).

Sam, aged 8, added: ‘I need safe housing, I need life to be predictable’. Instability in living circumstances may be particularly challenging for children who are neurodiverse – including those who have ASD and/or ADHD, as Sam disclosed – for whom structure is a source of comfort (McLean, 2022).

They understood what I ndded because of my disability

Feeling comfortable and safe

Only half of responses (50%, n=13) indicated that children and young people felt comfortable speaking with the service. Sam, aged 8, exposed an assumption inherent in framing of the prompt itself: ‘I like the option not to talk. I prefer play.’

Just over half of responses (54.2%, n=13) attested to children and young people feeling safe in their service engagement.

Four responses (16.7%) were from participants who did not feel safe. They explained:

I felt safe with some of the people but not with housing. It does not matter how nice some people are if I am moving from one scary situation to another [Sam, 8]

At first I did [feel safe], but in the end what happened made me very scared and made me feel unsafe [Darren, 13]

I felt comfortable talking to them

I felt safe

Some participants reflected on services’ inability to ensure their safety. Lisa, aged 11, described being supported by the service to create of a safety plan, only to be left on their own to confront the person using violence: